Jumping is one of the oldest disciplines in athletics. Both long jump and high jump are included in the school physical education curriculum. A high level of jumping helps improve technique in volleyball, basketball, tennis and a number of other sports. Athletes often combine strength training with jumping to make training more multifaceted, helping to develop not only strength, but also agility, flexibility, and speed. Long jumps help develop speed, pushing power, and coordination. You can long jump from a running start or from a standing position, and in these two cases the jumping technique will be slightly different.

Content

- 1 Standing long jump

- 2 Long jump 2.1 History of the long jump

- 2.2 Running long jump technique

- 2.3 Objectives when teaching the running long jump technique and their methodological orientation 2.3.1 Introduction to the running long jump technique

- 2.3.2 Pull-off technique combined with “step” flight

- 2.3.3 Push-off technique combined with a run-up

- 2.3.4 Movements in flight. Legs bent method

- 2.3.5 Scissors method

- 2.3.6 Landing technique in long jump

- 2.3.7 Long jump technique in general

Long jump[edit | edit code]

Source: Athletics

, 2016

History of the long jump[edit | edit code]

Long jump

- a discipline of athletics in which the ancient Greeks competed. The long jump was one of the Greek all-around events (pentathlon). Athletes of that time ran along a special track with dumbbells in their hands, suggesting that this could improve the result of the jump.

The counting of unofficial records (before the advent of the IAAF) in this type of athletics began with a result of 5.94 m, shown by the Englishman E. Bourke in 1857. After 17 years, the seven-meter line was overcome for the first time, and beyond eight meters (8.13 m) for the first time American D. Owens jumped in 1935. His world record lasted until 1960, and to this day you can win major international competitions with this result!

In 1968, at the Olympics in Mexico City, the American B. Beamon set a phenomenal record of 8.90 m. Then, according to experts, he made a “leap into the 21st century.” Only in 1991, the American M. Powell exceeded this result by 5 cm - 8.95 m, which is still a world record.

The greatest success among domestic long jumpers was achieved by I. Ter-Hovhannisyan; before B. Beamon’s jump, he held the world record of 8.35 m.

The first world record for women was recorded in 1928 and belonged to the Japanese athlete K. Hitomi (5.98 m). In 1939, it was improved by the German K. Schulz, who for the first time broke the six-meter mark (6.12 m). A result of more than 7 m (7.07 and 7.09 m) was achieved in 1978 by the Soviet athlete V. Bardauskene, and ten years later G. Chistyakova (USSR) sets a world record (7.52 m), which has not been surpassed to this day time. The winners of the Olympic Games were Soviet athletes V. Kretina (1960) and T. Kolpakova (1980).

At the 2004 Olympic Games in Athens, T. Lebedeva (Russia) became the champion among women - 7.07 m. Next to her on the podium stood two more Russian athletes - I. Simagin (II place) and T. Kotova (III place).

At the Olympic Games in London (2012), G. Rutherford (Great Britain) celebrated victory among men with a score of 8.31 m, and B. Rees (7.12 m, USA) among women. Russian athlete E. Sokolova was content with a silver medal, losing to the champion by 5 cm!

Running long jump technique[edit | edit code]

Main article:

Long jump technique

The long jump, despite the naturalness of the movements and seeming simplicity at first glance, is a rather complex exercise. The complexity is due to the fact that the jump consists of a series of non-repetitive actions by the athlete, performed with maximum power. Moreover, to achieve the greatest effect, all the actions of the jumper must have a close functional relationship and interdependence.

In long jumps, just like in other types of jumps, there are four parts: run-up, take-off, flight and landing.

In accordance with the movements performed in flight after take-off, the following methods of running long jump are distinguished: “bent legs”, “bend over” and “scissors”.

In general, the effectiveness of the long jumper’s movement technique is expressed in the following:

:

a) if possible, gain the highest speed during the run in the last two steps and maintain it at the moment of take-off;

b) in repulsion, have the ability to change the horizontal movement of the body to the optimal angle, maintaining the initial speed of departure;

c) continue in accordance with the chosen method of movement in flight and prepare for landing;

d) when landing, try to move your feet as far forward and higher as possible, preventing you from falling back after touching the ground.

Takeoff run

.

The main task of the run-up is to gain a high horizontal speed of movement of the jumper and make a restructuring in the structure of movements that helps create better conditions for taking off.

The second important characteristic of the long jump run-up is the accuracy of hitting the take-off point. The accuracy of the take-off run depends on: a) the standard take-off run length; b) a stable starting position of the jumper at the beginning of the run; c) identical execution of the first steps and a constant monotonous increase in the tempo of movements in the last steps of the run. It is also necessary to take into account meteorological conditions, such as headwinds and tailwinds, the surface and condition of the track, as well as the readiness of the athlete.

Currently, the best long jumpers tend to increase the length of their run-up and the number of running steps to develop the greatest speed before take-off. Jumpers use a run-up length of 40-50 m (for women - 35-40 m), consisting of 19-24 running steps (18-21 for women). With this length, by the end of the run, the running speed is 98-99% of the maximum. Moreover, in the practice of sports, there is an opinion that it is necessary to achieve not the maximum speed for a given athlete, but the so-called “controlled” one, when the duration of the run-up should be increased by 0.1-0.2 s. In general, the length of the run depends on the athlete’s height, his running and jumping fitness, and most importantly, on his ability to accelerate while running.

The starting position for the start of the run for one jumper must always be the same. The most common are two options: a) one leg in front, the torso is tilted, the arms are lowered, the movement begins with an energetic bend and active movement of the legs and arms; b) legs together, torso tilted, arms down or resting on knees, movement begins by “falling” forward. These starting positions allow you to start your takeoff fairly stably, and therefore more accurately approach the take-off bar.

Currently, three main options for the dynamics of takeoff speed are used: a) a gradual increase in speed at the beginning of the takeoff with a significant increase at the end; b) intensive increase in speed in the middle of the run and “free running” at the end; c) a quick start, maintaining speed in the middle and intensively increasing speed before take-off. The third option is preferable, which allows you to achieve maximum speed precisely at the moment of placing the pushing leg at the place of repulsion.

The first part of the run resembles a sprinter running from a low start: the torso is tilted forward, the arms work energetically. By the middle of the run, the torso straightens, the amplitude of movements of the arms and legs increases. For greater accuracy in the run, the jumper makes a control mark, which he must hit with his pushing foot four or six running steps from the block. After hitting this mark, the jumper should aim himself at the take-off bar.

When approaching the push-off, a restructuring of the movement system is observed in connection with the natural (unconscious) preparation for it, which is expressed in a slight decrease (from 6 to 12 cm) in the position of the athlete’s GCMT. In practice, this decrease is called a “squat”; its value is determined by the angle in the knee joint at the moment of vertical at the penultimate step and ranges from 105 to 136°.

It should be noted that it is necessary to avoid excessive squatting on the fly leg on the penultimate support, which leads to a significant decrease in the take-off speed during this period. In addition, the penultimate step of the run-up should be 20-30 cm longer than the last one. It is believed that such an increase in the length of the penultimate step is a necessary condition, and it is this that ensures the jumper takes off at the optimal angle. With a longer last step, the pushing leg is planted from the heel, and the take-off acquires a character close to a high jump. Preparation for the take-off itself begins with the penultimate step, when the athlete, as it were, lays the foundation for his take-off. At this moment, it is recommended to actively move forward (“run away” from the swing leg at the last step), without deflecting the body, and, maintaining horizontal speed, “run” onto the block. This psychological adjustment of the jumper helps to perform the final movements of the run-up most correctly and effectively.

Thus, the run-up is an important part of the long jump, which largely determines the result. The effectiveness of a jumper's actions during the run-up lies in the development of the highest running speed in the last 2-4 steps while maintaining the ability to take off.

Repulsion

.

The run-up ends with the placing of the pushing leg in the place of take-off, and from this moment the athlete begins to perform one of the most important parts of the long jump - take-off. The task of repulsion is to create the necessary direction of movement of the center of gravity with the least loss of horizontal movement speed and to help maintain a stable body position in flight.

Changing the direction of movement creates an optimal departure angle (18-24°), providing the required altitude and flight range.

Due to the transience of repulsion during its execution, any correction of movements becomes impossible. Therefore, its effectiveness largely depends on the accuracy and correctness of movements in the pre-push steps.

The leg is placed on the bar almost straightened at the hip and knee joints from the heel with a quick roll to the entire foot or to the full foot with an emphasis on its outer arch. In this case, the sound (“slap” of the foot) during the setting of the leg indicates either its passive setting, or weakness of the muscles of the ankle joint. Placing a straightened leg on a support helps the athlete’s CVMT to begin to rise upward immediately after the foot touches the track.

It should be noted that far exposure of the leg is always associated with significant losses of forward movement and a decrease in the initial take-off speed. Much more advantageous, from the point of view of maintaining speed, is the recommendation for a “raking” position of the leg, when it is placed as close as possible to the projection of the center of gravity on the plane of support. However, if the position is too close, there is a danger of insufficient take-off: the athlete does not have time to develop the forces necessary for take-off and, as a result, the vertical speed drops, which reduces the result. Important, from the point of view of reducing negative (stopping) horizontal forces at the moment the foot touches the track, is the speed of the foot itself relative to the track (zero speed at this moment seems ideal).

After placing the leg on the support, its shock-absorbing flexion begins, which is less pronounced in highly qualified athletes. Extension of the pushing leg begins as it approaches the vertical. Since the foot is placed on the push-off in front of the center of gravity (about 40 cm), the rapid movement of the fly links, which accelerates the movement of the center of gravity horizontally to the support point and beyond it, will be of great importance in reducing the loss of horizontal speed.

The swing leg, strongly bent at the knee joint, which leads to an increase in the angular velocity of the swing, is quickly moved forward, promoting the advancement of the pelvis. The “exit” of the pelvic area to the pushing leg is always accompanied by elasticity and timely repulsion. The yielding work of the muscles is replaced by the overcoming one, and the jumper at this moment creates an average force of pressure on the support equal to 300-400 kg. The best jumpers achieve this thanks to a high level of speed-strength fitness, increased and concentrated efforts, active swing movements, the interconnection of all parts of the body and consistency in their work at high take-off speed.

During the push-off process, the leg first extends at the hip joint, then at the knee, and finally at the ankle. At the end of the take-off, the thigh of the fly leg takes a horizontal position, and the lower leg, moving forward, strengthens the swing, simultaneously creating conditions for balance in flight. In this case, it is necessary to pay special attention to the vertical position of the body, which facilitates the movement of the swing leg and precise work of the hands.

The arm, which is the same as the pushing leg, is extended forward and upward to the position of the elbow joint, slightly below the shoulder. The other hand is moved to the side and slightly back. These movements, together with the high hip lift of the swing leg, help maintain balance during the push-off. In addition, you should pay attention to the position of the head during repulsion. It is advisable that the chin be slightly raised and the gaze directed forward and upward. These recommendations are based on the fact that the head of a jumper flying in the air is like a rudder directing the movement of the body.

Thus, when pushing off, all parts of the jumper’s body generate a force directed forward and upward, and these forces must be brought into action in the shortest possible period of time. Scientific research has shown that the ratio of horizontal to vertical speed in a good long jump is very close to the ratio of 2:1 and, with an optimal launch angle, allows high-class athletes to raise their GCMT at the highest point of the flight parabola to a height of 1.5 m.

According to a number of trainers, the psychological attitude when taking off should “include” a good “running into the jump” with the focus not on placing the foot on the bar and pushing, but on performing a quick hip swing. In this case, it is necessary to direct efforts in pushing “through the pelvis into the shoulders.”

Flight

.

All movements in the flight part are subordinated to one common task: maintaining balance and creating a rational starting position for the most advantageous extension of the legs before landing.

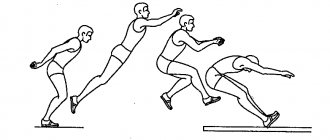

Long jump technique: A - “bent legs” method; B - by the “bending” method; B - “scissors” method

After taking off, at the beginning of the flight the jumper takes the following position: the pushing leg, having completed active work, bends slightly at the knee, and the fly leg, on the contrary, slightly extends at the knee joint; the arms drop slightly to the sides and help maintain the balance of the body in flight. This element of the jump, immediately following the take-off, is the same for all methods of running long jump and is called a “step” or “flight step” jump. In practice, depending on the subsequent movements made by the jumper in the unsupported phase, it is customary to distinguish the following main methods of jumping: “with legs bent.” “rotten” and “scissors”

.

However, it should be emphasized that the basis of any method is a quick run-up, active repulsion, wide reach and far throwing of the legs. All the variety of movements in flight lies between departure and grouping before landing. Therefore, it would be more correct to consider this variety not as methods of jumping technique, but as different options for maintaining balance in flight.

Jump with legs bent

is the simplest in terms of execution technique and teaching methodology.

It is usually used at the first stage of long jump training and is used mainly by low-skilled athletes. After taking off from the “step” position, the jumper pulls the pushing leg towards the fly leg, and both bent legs are pulled to the chest with the knees, and the torso is tilted forward.

At this time, the arms are lowered forward and down. At the end of the flight, about half a meter before landing, the athlete straightens his legs at the knee joints, moves them forward as far as possible, and moves his arms down and back, which promotes greater extension of the legs. After your feet touch the sand of the pit, your legs bend at the knees, cushioning the landing.

The advantages of this method of jumping include the fact that the posture adopted after take-off practically does not change until landing, which makes it possible to concentrate well on taking the correct posture for landing and try to maintain it. The main disadvantage of this method is the possible rotation in flight, which significantly reduces the jump range. To reduce rotation, you need to maintain the “step” position longer, straighten your torso and raise your arms up in the first half of the flight.

Jump using the “bend over” method.

In this method, after pushing off and flying out in a “step,” the athlete, bending his body back, lowers the swing leg down and back, bringing it closer to the push leg, and therefore both legs are slightly behind. At the same time, the pelvis, moving forward, promotes flexion in the thoracic and lumbar region. At the same time, the arms are quickly moved to the sides and back or up and back and to the sides. In this deflection position, the athlete flies about half of the flight phase, performing movements first to deflection, and then to reverse bending, changing the position of the arms and legs. Before landing, the torso leans forward and the arms are extended forward, down and back. The stretched muscles of the front surface of the body allow you to bend vigorously and make it easier to throw your legs forward to land, which is the advantage of this method.

The disadvantage of this method can be considered: a) the presence of a long pause in flight in a bent position; b) the possibility of early deflection, which most often occurs at the moment of repulsion, which does not allow the push to be fully completed.

Jump using the scissors method.

With this method of jumping, running and flying are, as it were, a single motor act, united by a similar rhythmic structure, i.e. the athlete most naturally moves from a run to a jump, as if continuing running movements during the flight. The scissor style also creates optimal conditions for maintaining balance in flight, which allows you to overcome the horizontal rotation of the body after take-off and provides a comfortable posture for landing.

After the “step” position, the athlete lowers the relaxed swing leg, and it moves back, and the pushing leg is carried forward. At the same time, the pelvis moves forward, the torso leans back, and the position of the legs in the air changes. The arm, which is the same as the pushing leg, goes down and rises up in an arcuate movement; the other arm is extended forward in an arc over the top. The head is kept straight throughout the flight, and the athlete should direct his gaze forward and upward. This is because lowering the head prevents a wider reach and, as a result, causes the torso to drop early in flight, making it difficult to raise the hips before landing.

Depending on the length of the jump, the athlete performs 2.5 or 3.5 “steps” in flight. The movements of the jumper with the correct balanced body position should be free, without tension, wide, sweeping and reminiscent of running through the air. This is the greatest value of the scissor jump.

Long jump landing options

Some jumpers demonstrate a technique that is characterized by a combination of elements of the “bend over” and “scissors” techniques. Apparently, combining the advantages of both methods in one jump is the path that should be followed when improving the long jump.

Landing

.

The task of landing is to touch the sand in the hole as far as possible and, without losing balance, go forward or to the side

.

Having completed the movements aimed at maintaining balance in flight, the jumper begins direct preparation for landing. The position that an athlete takes before landing is called a tuck. The body is slightly tilted forward, the hips are pulled towards the chest (and not vice versa!). Then you need to put your feet together and straighten your legs so that they are parallel to the ground and your arms are pulled back. At the same time, it is very important not to lower your head and not look at the future landing site, thereby “bringing it closer.” At the moment of landing, the legs quickly bend at the knee joints and the pelvis moves forward low above the surface of the sand.

Exercises to help master the long jump technique

When the flight path is fully used, the jumper either sinks onto his buttocks behind the landing marks, or has difficulty moving forward or to the side. The jumper has to run or jump forward out of the hole only in those cases when he lowered his legs early and did not fully use the flight path. The effectiveness of landing also depends on the ability of the athlete to touch the sand with his heels in one place and move the rest of the body beyond the landing point. This is performed by qualified athletes: through a deep squat with legs wide apart; by bending the lower back and moving the pelvis forward from a deep squat position; falling to the side. The third option is considered the most profitable.

Tasks when teaching the running long jump technique and their methodological orientation[edit | edit code]

Introduction to the running long jump technique[edit | edit code]

| Means used | Guidelines |

| a) A short story about the jumping technique and its features ABOUT | The story includes brief historical information about the long jump, how it is performed and the rules of the competition. |

| b) Demonstration of the long jump technique with a short run-up | In an intelligible form, focus attention on individual parts of the movements and the correct ways to perform them, also using visual aids |

The push-off technique combined with flight in a “step”[edit | edit code]

| Means used | Guidelines |

| a) Push off from one step, bringing the pelvis forward and raising the swing leg. The arm of the same name as the pushing leg is carried forward, the other is pulled back | Standing on the flywheel, actively pushing forward, perform a pushing position with the entire foot or from the heel with a quick transition to its front part. |

| Pay attention to the active execution of the swing movement with the leg strongly bent at the knee joint | |

| b) Repeated jumps in a “step” along the track, pushing off with the pushing leg through the step. The same, for every third step | Perform in a column one at a time. Make sure that the swing is performed synchronously and that the pushing leg is fully straightened. Try to maintain the “step” position for a long time |

| c) Jump in a “step” with 2-3 run-up steps and landing on the swing leg. The same, with landing in a lunge position | Make sure that the pushing leg is fully straightened in all joints when completing the push-off. Land on the flywheel and continue running |

| d) Long jumps with 3-4 running steps over an obstacle (barrier, bar, elastic band). Also, with reaching an object (knee, head, hand), suspended after the take-off point, followed by running | An obstacle 50-60 cm high is located at a distance of half the length of the jump. Make sure that when pushing off, the swing leg, bent at the knee joint, is moved forward and upward from the hip with an energetic movement. Throughout the flight, the practitioner’s gaze is also directed forward and upward. |

Push-off technique combined with a run-up[edit | edit code]

| Means used | Guidelines |

| a) Running along the runway with a take-off designation | Gradually gain speed by increasing your running tempo. In the last step, actively push through and bring your pelvis forward |

| b) Long jumps with 7-9 run-up steps with an emphasis on quickly placing the foot at the take-off point | Monitor the “raking” position of the pushing leg at the place of take-off and the unity of the run-up and take-off |

| c) From 7-9 steps of the run-up, take off, taking a “step” position, and before landing, move the pushing leg forward, followed by active “throwing out” of the legs | Perform the last steps by running along the marks. Make sure that the push-off is directed forward and upward and that there is no excessive squatting before the push |

| d) Long jump, pushing off from the gymnastic bridge after 7-9 run-up steps | Place the bridge at a distance of 2-3 m from the pit, watch for an increase in the tempo of movements in the last steps of the run-up and active running through the swing leg before take-off |

Movements in flight. The “legs bent” method[edit | edit code]

| Means used | Guidelines |

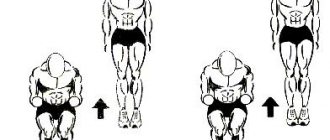

| a) Jump up from a place by pushing two legs over an obstacle with actively pulling the knees to the chest. The same, with a running start, pushing off with one leg | Gradually increase the height of the obstacle. Pay attention to the vertical position of the body in flight |

| b) Jumping in a “step” with 5-7 steps of run-up, followed by pulling the legs bent at the knees to the chest. The same, through vertical and horizontal obstacles | More than half the length of the jump must be flown in the “step” position. There is no need to rush into formation formation for landing. |

| c) Long jumps using the “legs bent” method with increasing run-up length, pushing off from the bridge, from the path in front of the pit and from the block | Pay attention to the activity of the swing movements, the high position of the knees when tucked before landing |

Scissors method[edit | edit code]

| Means used | Guidelines |

| a) Demonstration of leg movements using the scissors method | Demonstration and explanation of hanging on the crossbar or rings, in support on the uneven bars |

| b) From a short run-up, jump in a “step”, landing on the swing leg and then running. The same, but with a change in the position of the legs in flight, landing in a “step”, pushing in front | When performing the exercise, focus on the first step, which should be wide and active, which is achieved by moving the pelvis forward. The fly leg goes down and back in flight |

| c) While hanging on the bar or rings, imitate the movements of the legs in flight, bringing them forward and then jumping on both legs | Change the position of the legs without haste, moving from the hip with a large amplitude. Provide insurance when jumping |

| d) Imitation of hand work in place and while walking | Make sure that hand movements are performed widely, freely and are brought to automaticity |

| e) From a short run-up, jump using the “scissors” method, pushing off from the gymnastic bridge | Pay attention to the coordinated movement of the legs and arms, to maintaining balance in flight. To gain extra height, you can use jumps from an elevated support instead of a bridge. |

Landing technique in long jump[edit | edit code]

| Means used | Guidelines |

| a) Standing long jump with legs thrown far forward | Push off with both legs and one. Pay attention to the active movement of the knees forward and upward before landing |

| b) Throwing the legs into the pit from a sitting position in support on the lower bars of the barriers | “Take over” the feet. Installation on active raising of legs to chest |

| c) Long jump with a short run-up over an obstacle | A safe obstacle 30-50 cm high at a distance of 60-100 cm from the take-off point. Ensure timely grouping before landing |

| d) Running jumps in 5-7 running steps in the chosen way using a landmark, beyond which the practitioner must extend his legs | Before landing, raise your legs high and extend them as far as possible, even landing on your buttocks |

Long jump technique in general[edit | edit code]

| Means used | Guidelines |

| a) Running in the rhythm of a run-up with a push-off designation | Running over a distance equal to the length of the run on a treadmill. Increase the speed of movement until the moment of repulsion |

| b) Running run of 12-20 steps with an emphasis on running up in the last steps with pushing off from the bar | Gradually increase the length of the run-up by 2 steps so that you always start the run-up from the same foot. When repeating, adjust the accuracy of your foot hitting the bar for take-off |

| c) Long jumps with a full run-up, pushing off from the gymnastic bridge, and then from the bar for maximum results | Pay attention to the straightness and accuracy of the run-up, the rhythm of the last steps, “running into a jump”, take-off in a “step”, movements in flight, tuck and landing |

Dos and don'ts during practice

The following points should be on your checklist while practicing −

- Until the takeoff point, maintain speed at all costs.

- As soon as you cross the board, increase your speed sharply.

- To maintain a more upright position, experiment with your running styles that work best for you.

- The compensatory action of the weapon must be done to give impetus.

- Landing exercises should be added to the training schedule.

Until the takeoff point, maintain speed at all costs.

As soon as you cross the board, increase your speed sharply.

To maintain a more upright position, experiment with your running styles that work best for you.

The compensatory action of the weapon must be done to give impetus.

Landing exercises should be added to the training schedule.

Here's what you shouldn't do:

- Just before takeoff, shortening or lengthening your stride.

- Without gaining much speed, take off from the hill.

- Tilt the trunk too far forward or backward.

- Imbalance during flight.

- The position of one leg lower than the other during the landing phase.

Just before takeoff, shortening or lengthening your stride.

Without gaining much speed, take off from the hill.

Tilt the trunk too far forward or backward.

Imbalance during flight.

The position of one leg lower than the other during the landing phase.

It is advisable to effectively practice sail technique to improve takeoff technique. Through this practice the upright torso will be maintained and the position of the free leg will be improved.

We can divide the basic jumps into three separate sections −

- An approach

- Take off

- Flight

Let's discuss these methods in detail and try to understand how to effectively apply them in our practice.

Exercises for independent mastery of rational technique[edit | edit code]

Long jump

- Push-off from one run-up step with the pelvis moving forward and the swing leg lifting. The arm of the same name as the pushing leg is carried forward, the other is pulled back.

- Jump “in step” with 2-3 running steps, landing on the swing leg. The same in depth or with landing in a lunge position.

- Long jumps with 3-4 running steps over an obstacle (40-60 cm); the same with reaching an object (knee, head, hand) suspended after the place of repulsion.

- Running along the runway, gradually picking up speed, and indicating take-off. Perform a push-off in the last step on an elastic foot, actively pushing through and bringing the pelvis forward.

- Taking off after taking off from a short run-up in the “step” position, followed by lowering the swing leg down and landing on it. After landing, continue running on the sand.

- While supporting yourself on parallel bars or hanging on a bar, imitate the movement of your legs in flight, bringing them forward. Do not rush to change the position of your legs.

- Standing jump with two legs over an obstacle with active pulling of the knees to the chest. The same with a running start, pushing off with one leg (the “bent legs” method),

- Long jump from a short run-up with changing leg positions in flight (the “scissors” method). Make sure that the movements in flight are made from the hip, and not from the shins or straight legs alone.

- Long jumps from a short and medium run-up in various ways from a small elevation.

- Long jump with a short run-up to the designated landing spot, throwing your legs forward as far as possible and lowering your arms down and back. The same thing, landing on the buttocks, “take over” the soles of your feet.

- Jump with 3-5 running steps, directed more upward, landing on both feet in the first “step” position, and then in the second “step” position.

- Improving the technique of individual parts of the jump and performing jumps from a full run-up in a chosen way, trying to gain maximum speed in the run-up in the last meters before the take-off bar.

Typical execution errors

It is very easy to make mistakes during the exercise. Moreover, they are found in both schoolchildren and athletes.

Making mistakes is not scary, but not correcting them is scary.

If after a long period of training you are unable to do anything, try to find the mistake in your technique. The most common mistakes are presented below.

- Not warming up before training is very important for your safety. A few minutes can save your ligaments and knees from injury.

- The movements of the arms and legs are inconsistent with each other. Stand in front of a mirror and try to perform the movements while standing still.

- When landing, your legs drop earlier than they should. The reason may lie in weak abdominal or back muscles.

- The knees do not fully extend when taking off, which reduces the force of the jump. This happens when you are in a hurry.

- The body stands straight rather than pushed forward, which is why the jump is directed in height rather than in length.

- When landing, the jumper falls and falls backwards. You need to learn to group yourself in the air, straighten your legs towards the ground early and, after landing, throw your arms forward to maintain balance.

- Poor general physical fitness of the athlete - weak legs, lack of flexibility, problems with controlling his own body.

Ask someone knowledgeable to evaluate your technique from the outside to suggest your mistakes. If you have no one to turn to, record the training on video and watch it at home with an open mind.

Do stretching exercises, jog and do more knee lifts. Work your upper body muscles. Watch recordings of the performances of professional athletes, as you can only learn from the best how to jump far from a standing position.