To perform any basic exercise, proper technique is required. It is for the correct position of the body that both driving and stabilizer muscles are involved in the exercise. Their tone affects not only the technique of movement, but also the posture, as they hold the skeleton. Proper strengthening of the stabilizer muscles will help improve the quality of basic exercises and the functions of the musculoskeletal system outside of training.

Stabilizer muscles[edit | edit code]

Muscle stabilizers

- these are the muscles that are responsible for the equilibrium position of parts of our body relative to each other during the exercise. Some people think that these muscles need to be trained specifically, others think that there is no need for this. But we must admit that stabilizer muscles have a very important influence on your strength and exercise technique. Let's try to understand this issue.

Muscles can be divided into two types: MOTORS and STABILIZERS.

ENGINES

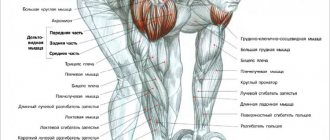

- These are the muscles that perform the main muscular work during strength exercises. Those. They are the ones who MOVE the parts of the skeleton relative to each other. For example, when performing a bench press, you move the humerus relative to the sternum (chest). This MOVEMENT is mainly carried out by the muscles of the CHEST, TRICEPS and anterior deltas. All of them will be engines.

STABILIZERS

- these are muscles that fix (STABILIZE) the position of parts of the skeleton relative to each other, but do not participate in movement.

In other words, these muscles perform a STABILIZING FUNCTION and do not directly participate in lifting weights. What are the benefits of them? These muscles provide STABILITY to the body parts for the proper functioning of the ENGINE MUSCLES. Well, since these muscles themselves do not carry out movements, then we can talk about ISOMETRIC (and not dynamic) contractions. By the way, precisely because these muscles do not perform dynamic work (they do not move bones), we often forget about them. It is very easy to forget about what is invisible.

To complicate the situation, most of these muscles are small or located deeper in the body than the muscles we are used to. Not only do these muscles work in an isometric mode (they do not move parts of the skeleton towards each other), but they are also small.

Moreover, depending on the exercise being performed, the STABILIZERS and MOTORS may change places. Which makes the situation even more confusing. For example, the back extensors will be MOTORS during hyperesthesia, and STABILIZERS during standing swings. And, for example, during squats with a barbell, formally STABILIZERS, but in practice the load on them will fall like on engines.

Most often, stabilizer muscles are smaller than motor muscles and therefore, theoretically, can fatigue faster. On the other hand, bodybuilding theory recommends starting the program with more basic exercises (where more stabilizer muscles are involved) and ending with more isolated exercises (where fewer stabilizer muscles are involved).

You need to start training with the most basic exercises that involve many stabilizer muscles. A departure from this rule is permissible, in my opinion, in conditions of a low-calorie diet, when you are weaker than usual. In such a situation, the use of insulation is acceptable.

Toward the end of the workout, you can use more isolation than at the beginning because the desired level of stimulation has already been received and tired stabilizers can prevent stress from deepening.

It is often recommended to start work with insulation (in order to tire out the engines but leave the stabilizers “fresh”), and end with the base (in such conditions, it seems that the stabilizers will not interfere with loading the engines). Personally, I am against this approach. I believe that if a person has weak stabilizers, then he should not lighten the load on them, but rather involve them in work from the very beginning of training. If you don’t do this, not only will your muscles grow worse (due to a weaker nerve impulse), but the likelihood of injury will also significantly increase. the balance of muscle contractions is disturbed.

Author of the article: Denis Borisov

Contraindications

Gymnastics to strengthen the muscles of the back and spine is contraindicated in the following cases:

- exacerbation of chronic pathologies or acute infectious processes;

- serious diseases of the body (oncology, renal failure, hypertension, etc.);

- spinal injuries;

- bleeding;

- severe pain syndrome.

Pregnant women and people who have recently undergone surgery should not perform back strengthening exercises.

Development of stabilizer muscles[edit | edit code]

Source: "Training Programs"

, scientific ed.

Author:

Professor, Doctor of Science Tudor Bompa, 2016

Propulsion muscles work more effectively when combined with strong stabilizer or anchor muscles. Stabilizer muscles contract primarily isometrically to stabilize a joint so that an action can be performed by another part of the body. For example, during elbow flexion, the shoulders are fixed in a stationary position, and the abdominal muscles act as stabilizers when throwing a ball with the hand. When rowing, when the muscles of the torso act as stabilizers, the torso transfers the power of the legs to the arms as the oar passes through the water. Accordingly, weak stabilizer muscles block the ability of driving muscles to contract.

If the stabilizing muscles are not properly developed, the core muscles may also become impaired. With chronic exercise, spasm of the stabilizer muscles may occur, which limits the work of the moving muscles and reduces the athlete’s performance. A similar situation is often observed in volleyball players who are injured as a result of poor muscle strength and imbalance in the muscles of the shoulder girdle[1]. The infraspinatus and supraspinatus muscles of the shoulder girdle are responsible for rotating the arm. The simplest and most effective way to strengthen these muscles is to rotate your arms with dumbbells. As a result of the resulting resistance, two muscle groups that stabilize the shoulder are stimulated. External (external) rotation of the hip joint is carried out due to the work of the piriformis and gluteus medius muscles. To strengthen these muscles, the athlete must take a standing position with fixed knees and lift the leg to the side using the load from the crossover exercise machine.

Stabilizing muscles also contract isometrically, resulting in immobilization of one part of the limb and movement of the other. In addition, these muscles control the interaction of the long bones in the joints and signal the risk of injury as a result of improper exercise technique, improper strength, or spasms that occur due to lack of stress management. If one of these conditions is met, the stabilizer muscles limit the work of the prime mover muscles, preventing the risk of strain or injury.

The above suggests that stabilizer muscles play an important role in improving the performance of athletes. On the other hand, some strength and conditioning coaches have recently placed too much emphasis on developing stabilizer muscles, especially through proprioception training (also called balance training). In fact, training on an unstable surface causes activation of the upper motor units as a result of simultaneous muscle contraction (meaning the simultaneous contraction of agonist and antagonist muscles to stabilize the joint), which does not lead to the neuromuscular adaptations that are necessary for athletes participating in speed-strength sports. These athletes require that antagonist muscles (i.e., passive muscles) be at rest during forceful activities.

On the other hand, many studies have shown that proprioception training using balance boards helps strengthen unstable or previously injured ankles[2][3][4]. Current theory suggests that if balance board training improves stability by improving proprioception and strengthening the stabilizer muscles of an unstable structure, the training will also provide further muscle strengthening and reduce the risk of muscle injury by providing a stable structure. However, this effect has not yet been proven, and the question of how much time should be devoted to exercises designed to strengthen stabilizer muscles remains unresolved.

Some studies suggest that proprioception may reduce the risk of knee injury[2], while other studies argue against the usefulness of proprioception training as a means of injury prevention[5]. In particular, a recent peer review study examined pitfalls in the design and implementation of proprioceptive learning outcomes[6]. Additionally, reports from strength and conditioning coaches who completely ignored the use of balance boards or proprioceptive training in team sports (soccer and volleyball) suggest that knee and ankle injuries remained unchanged in over the past 10 years.

Taking into account the above, we can conclude that training using a gymnastic ball or balance board can be useful in the early stage of the preparatory stage (anatomical adaptation stage). Of course, unilateral exercises are the optimal choice for improving joint strength while training the prime mover muscles. Proprioception training is good for the anatomical adaptation stage, but at a later stage the exercise ball and balance board should be put aside to free up time to train the athlete using techniques that directly improve his physical condition and promote the development of specific strength, speed and endurance. In general, even if the athlete’s proprioception has improved as a result of the exercises, the regularity and slowness of these exercises do not protect the joint from sudden and powerful movements performed during sports [7]. Preparing the stabilizing muscles for movement plays an important role: in particular, to ensure high performance and optimal fitness of the athlete, it is vital to train the movements specific to a particular sport at the appropriate level of specific speed, strength and endurance.

The table shows the breakdown of a young football player's work schedule over three weeks during the macrocycle of anatomical adaptation. Pay attention to the large number of unilateral exercises, the same amount of work performed by the agonist and antagonist muscles, the duration of the sets under load, which does not exceed the range of the lactate system (from 48 to 80 seconds), gradually increasing the load and shorter duration macrocycle, which is typical for young athletes and professionals. Below is a point-by-point description for each column in the figure:

- sets: each number represents the number of sets performed during a particular week. For example, 2-3-2 means two sets are performed during the first week, three sets during the second week, and two sets during the third week;

- Repetitions: Each number represents the number of repetitions performed during a particular week. For example, 20-15-12 means 20 reps per set are performed in the first week, 15 reps per set in the second week, and 12 reps per set in the third week;

- Rest Break: Each number represents the length of rest between sets of exercises for a given week. For example, 1-1-1.5 means that during the first week the rest break between sets lasts one minute, during the second week - one minute, during the third week - one and a half minutes.

- repetition time: the first digit displays the duration of the eccentric phase in seconds, the second digit displays the pause between the eccentric and concentric phases, and the third digit displays the duration of the concentric phase (X indicates the explosive phase);

- Load: These columns are used to record the weekly load for each set of each exercise.

Rough breakdown of a young football player's three-week work schedule during the macrocycle of anatomical adaptation

| Exercise | Approaches | Repetitions | Rest break (min.) | lead time | LOAD | ||

| 1 Week | 2 week | 3 week | |||||

| Workout A | |||||||

| Single leg squats | 2-3-2* | 20-15-12* | 1-1-1,5* | 3-0-1** | |||

| Single leg curl | 2-3-2 | 20-15-12 | 1-1-1,5 | 3-0-X | |||

| Single leg deadlift | 2-3-2 | 20-15-12 | 1-1-1,5 | 3-0-1 | |||

| Extension of the gluteal muscles and quadriceps | 2-3-2 | 20-15-12 | 1-1-1,5 | 3-0-1 | |||

| Working with abductor muscles on the simulator | 2-3-2 | 20-15-12 | 1-1-1,5 | 3-0-1 | |||

| Working with adductor muscles on the simulator | 2-3-2 | 20-15-12 | 1-1-1,5 | 3-0-1 | |||

| Standing calf raise | 2-3-2 | 20-15-12 | 1-1-1,5 | 2-2-1 | |||

| Crunches using weights | 2-3-2 | 20-15-12 | 1 | 3-0-3 | |||

| Workout B | |||||||

| Dumbbell supine press | 2-3-2 | 20-15-12 | 1-1-1,5 | 3-0-1 | |||

| Dumbbell row | 2-3-2 | 20-15-12 | 1-1-1,5 | 3-0-1 | |||

| Seated dumbbell press | 2-3-2 | 20-15-12 | 1-1-1,5 | 3-0-1 | |||

| Dumbbell biceps curl | 2-3-2 | 20-15-12 | 1-1-1,5 | 3-0-1 | |||

| Front and side elbow stand | 2-2-1 | 30-30—45 (sec.) | 0,5 | Isometric | |||

*For each triple of digits in this column, the first digit refers to the first week, the second digit refers to the second week, and the third digit refers to the third week.

**In each triple of numbers in this column, the first number represents the duration of the eccentric phase in seconds, the second number represents the duration of the pause between the eccentric and concentric phases, and the third represents the duration of the concentric phase (X indicates the explosive phase).

FAQ

Will exercise therapy help you recover faster after a hernia removal?

Yes, it will help. The main thing is to strictly follow all the doctor’s advice, do not rush, and do not increase the load ahead of time.

Is it possible to do exercise therapy for Schmorl's hernia?

Yes. Exercise therapy can be done for any type of hernia, when the acute pain subsides. The main thing is to choose the right set of exercises. If you have a Schmorl's hernia, you definitely need to pump up and strengthen the muscles, especially the back and abdomen. It is important to remember: weight bearing is contraindicated.

Is it possible to do exercise therapy for a sequestered hernia?

It is possible, but we must proceed from the fact that exercise therapy cannot be done during the acute phase. When the pain subsides, light exercise is allowed after consulting a doctor. Water gymnastics gives a good effect.

Themes

Intervertebral hernia, Spine, Pain, Treatment without surgery Date of publication: 11/12/2020 Date of update: 03/16/2021

Reader rating

Rating: 5 / 5 (4)

Training with a gymnastic ball[edit | edit code]

Like any other object used in specific training, a gymnastic ball (also called a fitball) is nothing new. This element was first used in the 1960s, and since then it has gained wide popularity, especially when used for rehabilitation purposes. Since the 1990s, the gymnastic ball has also become widely used for sports and fitness. The popularity of this element in fitness is easily explained, given that the main characteristic features of this type of sports activity are a variety of exercises and pleasure.

Performing exercises using a gymnastic ball helps strengthen the muscles of the upper and lower body, develop overall flexibility and, of course, the core muscles. However, some representatives of the sports community, who argue that improving proprioception and balance have an impact on the overall performance of the athlete, overestimate the positive effect of these exercises. In fact, balance does not limit overall performance in any way and is a skill in a different category than speed, strength and endurance.

In addition to the above, athletes and coaches should be aware that working with an exercise ball during the maximal strength development phase can have a detrimental effect on the athlete's performance. The ball limits the amount of weight an athlete can lift because it requires more neural stimulation to stabilize the body as a whole, as well as individual joints, resulting in less activation of the fast-twitch fibers of the prime mover muscles. Accordingly, it is recommended to use only exercises with a gymnastic ball that are aimed at training the abdominal muscles and provide a complete stretch of the athlete's abdominal muscles to the concentric part of the exercise. There are more effective means for training other muscle groups.

Gymnastic balls should be used at certain stages of training. The process of overstimulation shows how all the muscles involved during a movement participate and interact. Our body is very flexible and adapts remarkably well to traditional training methods. More importantly, the performance of an athlete's body depends on the level of adaptation that creates natural resilience.

For what diseases are exercises indicated?

Not only to prevent back pain, it is recommended to do a number of strengthening exercises. Gymnastics for the lower back can, to some extent, help cope with a number of diseases in this area. For example, it is very effective for spondylosis. This pathology is usually observed in older people due to age-related changes in the structure of the spinal column. Most often, with spondylosis, the vertebrae change their shape quite significantly, becoming overgrown with spines and protrusions.

Symptoms of spinal spondylosis

Gymnastics for the lower back is also indicated for intervertebral hernias. They usually appear during significant physical exertion or due to a sedentary lifestyle, as well as due to sitting in an incorrect position.

Sources[edit | edit code]

- Kugler, A., Kruger-Franke, M., Reininger, S., Trouillier, H. H., and Rosemeyer, B. 1996. Muscular imbalance and shoulder pain in volleyball attackers. British Journal of Sports Medicine 30(3): 256-59.

- ↑ 2.02.1 Caraffa, A., Cerulli, G., Projetti, M., Aisa, G., and Rizzo, A. 1996. Prevention of anterior cruciate ligament injuries in soccer. A prospective controlled study of proprioceptive training. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy 4 (1): 19-21.

- Wester, J. U., Jespersen, S. M., Nielsen, K. D., and Neumann, L. 1996. Wobble board training after partial sprains of the lateral ligaments of the ankle: A prospective randomized study. Journal of Orthopedic & Sports Physical Therapy 23 (5): 332-36.

- Willems, T, Witvrouw, E., Verstuyft, J., Vaes, P., and Clercq, D.D. 2002. Proprioception and muscle strength in subjects with a history of ankle sprains and chronic instability. Journal of Athletic Training No. 1 (4): 487-93

- Soderman, K., Wener, S., Pietila, T., Engstrom. B., and Alfredson, H. 2000. Balance board training: Prevention of traumatic injuries of the lower extremities in female soccer players? A perspective randomized intervention study. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy 8 (6): 356-63.

- Thacker, S.B., Stroup, D.F., Branche, C.M., Gilchrist, J., Goodman, R.A., and Porter Kelling, E. 2003. Prevention of knee injuries in sports. A systematic review of literature. Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness 43(2): 165-79.

- Ashton-Miller, J. A., Wojtys, E. M., Huston, L. J., and Fry-Welch, D. 2001. Can proprioception be improved by exercise? Knee Surgery Sports Traumatology Arthroscopy 9(3):128–36.