This article uses anatomical terminology.

| This article need additional quotes for verification . |

| External oblique muscle | |

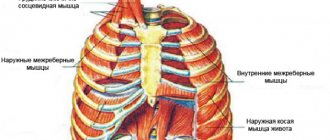

| Muscles of the trunk. | |

| External oblique muscle | |

| Details | |

| Source | Ribs 5-12 |

| Insert | Xiphoid process, outer lip, iliac crest, pubic crest, pubic tubercle, linea alba, inguinal ligament, anterior superior iliac spine (AS IS) |

| Nerve | Thoracoabdominal nerves (T7-11) and hypochondrium nerve (T12) |

| Actions | Torso flexion and contralateral rotation of the trunk |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Musculus obliquus externus abdominis |

| TA98 | A04.5.01.008 |

| TA2 | 2364 |

| F.M.A. | 13335 |

| Anatomical conditions of the muscle [edit in Wikidata] | |

B external oblique muscle

(also

external oblique

, or

external oblique

) is the largest and outermost of the three flat presses of the lateral front part of the abdomen.

Structure

The external braid is located on the lateral and anterior parts of the abdominal cavity. This is a wide, thin and irregular quadrangle, its muscular part occupies the side, the aponeurosis is the anterior wall of the abdomen. In most people (especially women), the oblique margin is not visible due to the thick deposits under the skin and the small size of the muscle.

It arises from eight fleshy fingers, each from the outer surfaces and lower borders of the fifth to twelfth ribs (the lower eight ribs). These fingers are located along an oblique line running from below and in front, with the upper fingers attached close to the cartilages of the corresponding ribs, the lowest ones to the top of the cartilage of the last rib, and the intermediate ones to the ribs in some places. distance from their cartilage.

The five upper teeth increase in size from top to bottom and are received between the corresponding processes of the serratus anterior muscle; the three lower ones decrease in size from top to bottom and receive corresponding processes from the latissimus dorsi muscle. Fleshy fibers extend from these attachments in different directions. Its posterior fibers from the ribs to the iliac crest form the free posterior edge.

The ribs from the lowest ribs extend almost vertically downward and are inserted into the anterior half of the outer lip of the rib. iliac crest; The middle and superior fibers, directed downwards (inferiorly) and anteriorly (anteriorly), become aponeurotic at approximately the level of the midclavicular line and form the anterior layer of the rectus sheath. This aponeurosis is formed from fibers on either side of the external oblique chiasm on the linea alba.

The aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle forms the inguinal ligament. The muscle also contributes to the inguinal canal.

The internal oblique muscle is simply deep within the external oblique muscle.[1]

Nervous nutrition

The external oblique muscle is supplied by the ventral rami of the six inferior thoracoabdominal nerves and the hypochondrium nerves on each side.

Blood supply

The cranial portion of the muscle is supplied by the inferior intercostal arteries, while the caudal portion is supplied by branches of either the deep circumflex iliac artery or the iliopsoas artery.

Diastasis of the rectus abdominis muscles - symptoms and treatment

Diastasis of the rectus abdominis muscles does not always require surgical correction. For women who are less than 12 months postpartum and overweight patients who have not previously tried to correct diastasis with exercises, it is recommended:

- control weight: body mass index (BMI) should not exceed 26 with an average build;

- do exercises to strengthen the anterior abdominal wall [1][8].

Exercises for diastasis

There is no single set of exercises; different trainers use different programs. It should be noted that all exercises are aimed at strengthening the muscular frame of the abdominal wall, but they do not always help reduce the width of the white line of the abdomen [8][10]. For diastasis, it is recommended to perform the following exercises:

- Supination (outward rotation) of the knee in a position on all fours . Starting position - emphasis on your knees and straightened arms. From this position, bend your left leg and bring your knee towards your sternum, then do the same with your right leg. You can perform 10 repetitions on each leg, 5-6 approaches per day.

- Exercise " plank " and its variations. The emphasis can be placed on your knees or toes, on your elbows or straightened arms. This is a static exercise; it does not lead to excessive muscle stretching. The execution time gradually increases from 20 seconds to 1 minute. Perform 3–5 approaches per day.

- Exercise "to the eye " . In a position on all fours, as you exhale, arch your back upward, rounding it like a cat, while straining and drawing in your stomach as much as possible. Keeping your muscles tense, exhale and slightly bend your back in the opposite direction. Do 10–15 repetitions, 3–4 sets per day.

- A set of Kegel exercises. They are aimed at strengthening the abdominal and pelvic floor muscles. Technically, these exercises are not difficult, but they must be performed carefully. If the technique is incorrect, the effect can be the opposite. It is recommended to do approaches 3-4 times a day for 10-15 minutes. As a rule, the effect appears after 4–6 weeks.

Classic exercises for strengthening the abdominal muscles with lifting and twisting the torso, including wall bars, can only increase diastasis and should be excluded. Young mothers can start exercising only 4–6 months after giving birth. During this time, connective tissue structures restore their strength.

According to some authors, up to 87% of patients remain dissatisfied with the results of training programs and require surgical treatment [11]. This is probably due to irreversible damage to the integrity of the tendon bundles of the white line of the abdomen.

Surgery

The goal of all diastasis surgeries is to eliminate the enlarged gap between the rectus abdominis muscles and strengthen the newly formed, thinner linea alba. Open classical or laparoscopic techniques, as well as interventions from mini-approaches, can be used. The results for all techniques are similar, so the choice of operation, as a rule, depends on the individual experience of the surgeon. All techniques can be used for the combination of diastasis recti and umbilical hernia [1][6][8][9].

Robotic surgery is more expensive and does not offer advantages over laparoscopic techniques, so it is not used as widely.

Open methods. Access to the extended linea alba is performed through an incision on the anterior abdominal wall: longitudinal above the midline or transverse below the navel if excess fatty tissue needs to be removed. The “fat apron” is removed to prevent suppuration of exfoliated fiber and improve appearance. The surgeon frees the edges of the internal oblique abdominal muscles from fatty tissue, brings them together using numerous individual or several continuous sutures, and then installs a mesh implant over the formed suture.

The operation is traumatic, after which the patient remains in the clinic for 5–7 days. Some authors report that there are no relapses when using open techniques, others report 4% or more relapses [9]. This operation is performed if it is necessary to remove the “fat apron”, and also if the surgeon does not have the skills to perform laparoscopy. In addition, this technique may be preferable when there is a combination of diastasis recti and an incisional midline hernia.

Laparoscopic techniques. The operation is performed through separate punctures on the abdominal wall. The surgeon and assistant, using special manipulators and a video camera, separate the linea alba from the preperitoneal fatty tissue from the abdominal cavity, and then strengthen it with one continuous or several separate sutures. When the diastasis is eliminated, the posterior surface of the abdominal wall can be further strengthened with a mesh implant. This technique can be used for a combination of diastasis and hernia of the white line of the abdomen. The recurrence rate of diastasis after laparoscopic plastic surgery of the linea alba does not exceed 2% [9]. However, using this technique it is impossible to eliminate the “fat apron” if it exists. This operation is carried out if the surgeon has the necessary skills and the technical capabilities of the medical institution.

Techniques using mini-accesses. This operation combines the positive qualities of open and laparoscopic methods for eliminating diastasis. A 4–5 cm long transverse incision is usually made below the navel at the level of the bikini line or directly above the navel (depending on the extent of the diastasis). Then, a channel is formed in the subcutaneous fatty tissue above the linea alba for the surgeon to work with. Viewing in the canal is usually carried out using a special video camera, as in laparoscopy. The surgeon also approximates the inner edges of the rectus abdominis muscles and then strengthens the anterior abdominal wall with a mesh implant [12]. The recurrence rate using the mini-approach is approximately the same as with open surgery. The technique is used if there are contraindications for laparoscopy (severe adhesive disease in the abdomen after surgery, severe chronic heart failure).

If the clinic has the necessary equipment and a qualified plastic surgeon, each technique can be supplemented with liposuction and liposculpture, in which excess fat is removed from certain areas of the abdomen and thus the relief of subcutaneous fat is formed.

Possible complications after surgery:

- Bleeding with the formation of a hematoma of the surgical wound or in the abdominal cavity. If the bleeding stops on its own, the hematoma does not increase, no blood comes from the wound and the patient feels normal, the hematoma is removed. If the bleeding continues, it must be stopped: remove several stitches and stitch or cauterize the bleeding vessel.

- Seroma of a postoperative wound. This is an accumulation of serous fluid in the thickness of the abdominal wall, namely in the area where the surgeon freed the linea alba from fatty tissue. It manifests itself as swelling and thickening of the subcutaneous fatty tissue. The seroma is removed by a surgeon in the dressing room. If the seroma suppurates, urgent hospitalization is required in the purulent surgery department. This complication is less common during laparoscopy [9].

- Suppuration of the postoperative wound and mesh implant. The operation site turns red and hurts, body temperature rises, chills and sweating appear, especially in the evening. With this complication, it is necessary to remove the pus from the wound and prescribe antibacterial therapy. It is often necessary to remove the mesh implant. It is not known exactly how often surgical wounds fester; according to some data, the complication rate can reach 2% or more [9]. Suppuration occurs due to the addition of infection, especially if there are foci of infection in the body: carious teeth, chronic tonsillitis, chronic inflammatory diseases of the urinary tract (cystitis, pyelonephritis) and female genital organs (salpingitis, endometritis).

- Severe pain in the wound area in the first month after surgery or longer than three months. The patient is concerned if nerve fibers are damaged or compressed during surgery. With such a complication, a second operation may be required: release of the nerve from compressive tissue, removal of the mesh implant, excision of the postoperative scar, removal of the sutures fixing the mesh implant [1][9]. Some authors report that chronic pain syndrome after open surgery can be detected in 17% of patients; laparoscopy can reduce this figure to zero [9].

It is not known exactly how often complications develop after surgery, since in most cases treatment is carried out in private clinics and complications are not included in registries. On average, the incidence of complications is up to 10–15% [9].

Additional images

- Rear view of the muscles connecting the upper limb to the spine. The posterior part of the external oblique abdominal muscle is indicated.

- Subcutaneous inguinal ring.

- Cross section through the middle of the first lumbar vertebra showing the relationship of the pancreas.

- Left side of the chest.

- Superficial anatomy of the anterior chest and abdomen.

- Lumbar triangle

- External oblique abdominal muscle. Anterior abdominal wall. Deep dissection. Front view.

Internal oblique muscle

The abdominal ECM is also a wide, thin muscle layer that lies deep to the abdominal ECM. It originates from the thoracolumbar fascia, the anterior two-thirds of the iliac crest and the lateral two-thirds of the inguinal ligament. The muscle fibers extend in a superomedial direction and attach to the lower borders of the lower three ribs and their costal cartilages, the xiphoid process, the linea alba and the pubic symphysis. Near their insertion, the lowest tendon fibers join with similar fibers of the transverse abdominis muscle to form a united tendon.

Innervation

The abdominal ECM is innervated by six inferior thoracic nerves, the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves.

Function

Unilateral contraction of the abdominal ECM results in ipsilateral lateral flexion and rotation of the trunk. This is achieved by contracting together with the abdominal muscle mass located on the opposite side. This muscle also helps increase intra-abdominal pressure, pushing internal organs up toward the diaphragm, resulting in forced exhalation.

In order not to miss anything interesting, subscribe to our Telegram channel.

Recommendations

This article incorporates public domain text from page 409 of the 20th edition

Gray's Anatomy

(1918)

- LeBlanc, Eric; Frumowitz, Michael (2018-01-01), Ramirez, Pedro T.; Frumowitz, Michael; Abu-Rustum, Nadim R. (ed.), "Chapter 8 - Surgical Staging for Treatment Planning", Principles of Gynecologic Oncologic Surgery

, Elsevier, pp. 116–126, doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-42878-1.00008- 0, ISBN 978-0-323-42878-1, received 2020-11-23 - Conte, S. A.; Thompson, M.M.; Marks, M.A.; Dines, J. S. (March 2012). "Abdominal Muscle Strain in Professional Baseball: 1991-2010." American Journal of Sports Medicine

.

40

(3): 650–6. Doi:10.1177/0363546511433030. PMID 22268233.

Transverse abdominis muscle

The transverse abdominis muscle is the deepest of the abdominal muscles, lying medially relative to the ECM of the abdomen. This is a thin layer of muscle, the fibers of which are directed horizontally and anteriorly. The transverse abdominis muscle arises as fleshy fibers from the deep surface of the lower six costal cartilages, the psoas fascia, the anterior two-thirds of the iliac crest, and the lateral third of the inguinal ligament. It connects to the xiphoid process, the linea alba and the pubic symphysis. The inferior tendon fibers join with similar fibers of the abdominal ECM to form a united tendon attached to the crest of the pubis and the pectineal line.

Innervation

The transverse abdominis muscle is innervated by the six inferior pectoral nerves, the iliohypogastric nerves, and the ilioinguinal nerves.

Function

Contraction of the transverse abdominis muscle has a corsetopod effect, narrowing and flattening the abdominal cavity. Its primary function is to stabilize the lumbar spine and pelvis before movement of the lower and/or upper extremities occurs.

Best exercises

A basic exercise for pumping up the external oblique abdominal muscle can be considered crunches with rotation. Lying on your back, using the strength of your abs, lift your upper body 15-20 cm up - then, as you exhale, make a neat turn, lifting the left side of your body a little higher and pointing your right elbow to the floor.

Note that the fundamental difficulty in choosing the most effective abdominal exercises lies in the fact that different people feel differently about the involvement of certain segments of the abdominal muscles in the work - in simple words, for everyone there is their own “best” abdominal exercise.

// Exercises for the oblique abdominal muscle:

- Side crunches on the back

- Lateral crunches on the side

- Lateral crunches on a fitball

- Crunches on a block while lying on a fitball

- Exercise “Lumberjack” on blocks

- Hanging leg raises with rotation

- Side press on the upper block

// How to pump up the side press - photos and descriptions of exercises

***

The external oblique is the largest of all the abdominal muscles. It is involved in any exercises involving bending or rotating the body. However, for proper training, it is important for beginners to perform exercises without additional weight.

There may be contraindications to physical exercise in general - and exercises to train the oblique abdominal muscle in particular. If in doubt, consult a specialist.

Data sources:

- Architectural Analysis of Human Abdominal Wall Muscles: Implications for Mechanical Function, source

- Physiopedia - External Abdominal Oblique, source

Operation technique

The procedure involves suturing the dislocated areas while maintaining mobility. At the same time, it is important to avoid the formation of transverse duplication, which can lead to dangerous postoperative complications in the form of repeated ruptures.

Operative access is created in the area of pain.

The surgeon repairs the dissection by placing sutures in a staggered pattern at a distance of 0.5 to 2 cm to avoid tension on the tendons.

Compliance with the intervention technique allows you to eliminate pain and limitations in mobility. Patients begin exercise therapy within two weeks.

Abdomen

Abdominal structure: muscles

The internal structure of the abdomen is represented by the abdominal cavity. The cavity is lined from the inside by peritoneum, which has internal and external layers.

Between the layers of the peritoneum are the abdominal organs, blood vessels and nerve formations. In addition, the space between the layers of the peritoneum contains a special liquid that prevents friction.

The peritoneum not only nourishes and protects the structures of the abdomen, but also anchors the organs. The peritoneum also forms what is called mesenteric tissue, which is connected to the abdominal wall and abdominal organs.

The boundaries of the mesenteric tissue extend from the pancreas and small intestine to the lower parts of the colon. The mesentery secures organs in a certain position and nourishes tissues with the help of blood vessels.

Some abdominal organs are located directly in the abdominal cavity, others in the retroperitoneal space. Such features are determined by the position of the organs relative to the layers of the peritoneum.